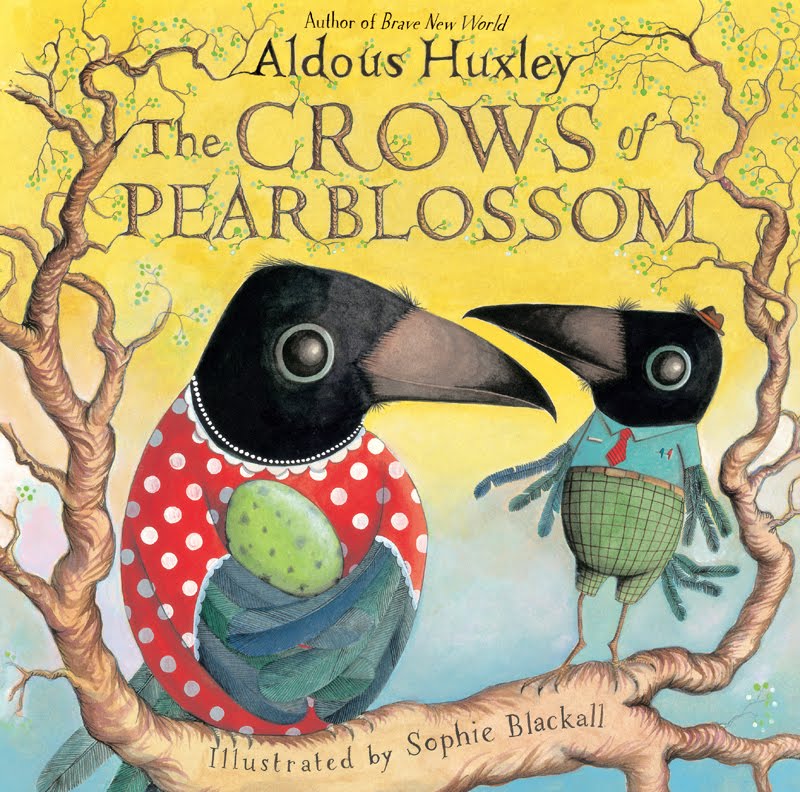

1. ALDOUS HUXLEY

Aldous Huxley

Aldous Huxley may be best known for his iconic 1932 novel

Brave New World, one of the most important meditations on futurism and how technology is changing society ever published, but he was also deeply fascinated by children’s fiction. In 1967, three years after Huxley’s death, Random House released a posthumous volume of the only children’s book he ever wrote, some 23 years earlier.

The Crows of Pearblossom tells the story of Mr. and Mrs. Crow, whose eggs never hatch because the Rattlesnake living at the base of their tree keeps eating them. After the 297th eaten egg, the hopeful parents set out to kill the snake and enlist the help of their friend, Mr. Owl, who bakes mud into two stone eggs and paints them to resemble the Crows’ eggs. Upon eating them, the Rattlesnake is in so much pain that he beings to thrash about, tying himself in knots around the branches. Mrs. Crow goes merrily on to hatch “four families of 17 children each,” using the snake “as a clothesline on which to hang the little crows’ diapers.”

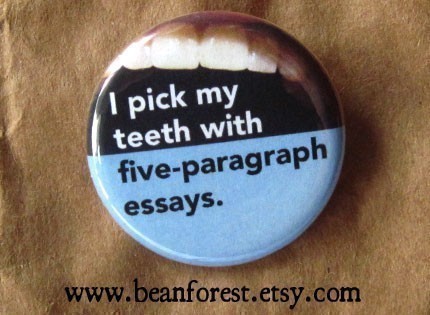

The original volume was illustrated by the late

Barbara Cooney, but a new edition published this spring features artwork by

Sophie Blackall, one of my favorite artists, whose utterly lovely

illustrations of Craigslist missed connections you might recall.

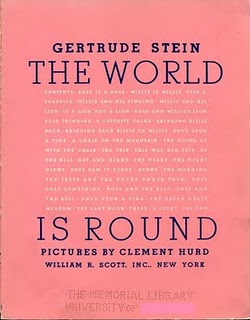

2. GERTRUDE STEIN

Writer, poet and art collector

Gertrude Stein is one of the most beloved — and

quoted — luminaries of the early 20th century. In 1938, author Margaret Wise Brown of the freshly founded Young Scott Books became obsessed with convincing leading adult authors to try their hands at a children’s book. She sent letters to Ernest Hemingway, John Steinbeck, and Gertrude Stein. Hemingway and Steinbeck expressed no interest, but Stein surprised Brown by saying she already had a near-complete children’s manuscript titled

The World Is Round, and would be happy to have Young Scott bring it to life. Which they did, though not without drama. Stein demanded that the pages be pink, the ink blue, and the artwork by illustrator Francis Rose. Young Scott were able to meet the first two demands despite the technical difficulties, but they Scott didn’t want Rose to illustrate the book and asked Stein to instead choose from several Young Scott illustrators. Reluctantly, she settle don Clement Hurd, whose first illustrated book had appeared just that year.

The World Is Round was eventually published, featuring a mix of unpunctuated prose and poetry, with a single illustration for each chapter. The original release included a special edition of 350 slipcase copies autographed by Stein and Hurd.

In 1942, despite resistance from her publisher, Stein followed up with a second book, the excellent

To Do: A Book of Alphabets and Birthdays, the latest edition of which came from Yale University Press earlier this year and is illustrated by the lovely

Giselle Potter.

The wonderful

We Too Were Children has the backstory.

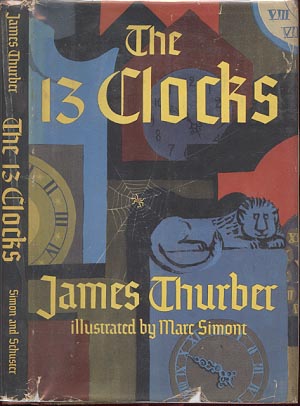

3. JAMES THURBER

In the 1940s and 1950s, celebrated American author and cartoonist

James Thurber, best-known for his contributions to

The New Yorker, penned a number of book-length fairy tales, some illustrated by acclaimed French-American artist and political cartoonist

Marc Simont. The most famous of them was

The 13 Clocks — a fantasy tale Thurber wrote in Bermuda in 1950, telling the story of a mysterious prince who must complete a seemingly impossible challenge to free a maiden, Princess Saralinda, from the grip of the evil Duke of Coffin Castle. The eccentric book is riddled with Thurber’s famous wordplay and written in a unique cadenced style, making it a fascinating object of linguistic appreciation and a structural treat for language-lovers of all ages.

For a cherry on top, the current edition features an introduction by none other than

Neil Gaiman.

Thanks, stormagnet

4. CARL SANDBURG

In 1922, nearly two decades before the first of his three Pulitzer Prizes, poet

Carl Sandburg wrote a children’s book titled

Rootabaga Stories for his three daughters, Margaret, Janet and Helga, nicknamed “Spink”, “Skabootch” and “Swipes,” respectively. Their nicknames occur repeatedly in some of the volume’s whimsical interrelated short stories.

The book arose from Sandburg’s desire to create the then-nonexistent “American fairy tales,” which he saw as integral to American childhood, so he set out to replace the incongruous imagery of European fairy tales with the fictionalized world of the American Midwest, which he called “the Rootabaga country,” substituting farms, trains, and corn fairies for castles, knights and royatly. Equal parts fantastical and thoughtful, the stories captured Sandburg’s romantic, hopeful vision of childhood.

In 1923, Sandburg followed up with a sequel,

Rootabaga Pigeons, telling tales of “Big People Now” and “Little People Long Ago.”

Thanks, Rachel

5. SALMAN RUSHDIE

Indian-British novelist

Salman Rushdie has had his share of

acclaim and

controversy, but one thing that has remained constant over his prolific career is his penchant for the written word. In 1990, he turned his talents to children’s literature with the release of

Haroun and the Sea of Stories — a phantasmagorical allegory for a handful of timely social and social justice problems, particularly in India, explored through the young protagonist, Haroun, and his father’s storytelling. The book received a Writer’s Guild Award for Best Children’s Book that year.

One of the book’s unexpected treats is breakdown of the meanings and symbolism of the ample cast of characters’ names, an intriguing linguistic and semantic bridge to Indian culture.

Twenty years later, just last winter, Rushdie followed up with his highly anticipated second children’s book,

Luka and the Fire of Life: A Novel.

Thanks, SaVen

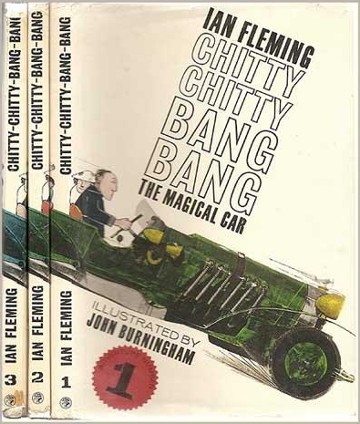

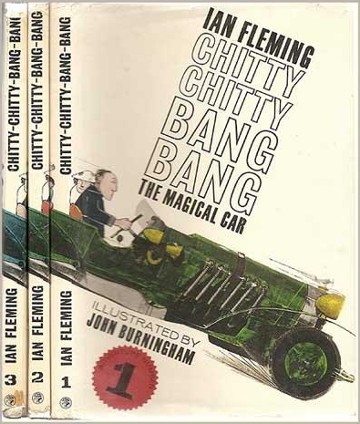

6. IAN FLEMING

Ian Fleming

Ian Fleming is best-known as the creator of one of the best-selling literary works of all time: the James Bond series. A few years after the birth of his son Caspar in 1952, Fleming decided to write a children’s book for him, but

Chitty Chitty Bang Bang didn’t see light of day until 1964, the year Fleming died. It tells the story of the Potts family and the father figure, Caractacus, who uses money from the invention of a special candy to buy and repair a unique, magical former race car, which the family affectionately names Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. Fleming’s inspiration came from a series of aero engines built by racing driver and engineer Count Louis Zborowski in the early 1920s, whose first six-cylinder Maybach aero engine was called Chitty Bang Bang.

The original book was beautifully illustrated in black-and-white by

John Burningham and was soon adapted into the 1968 classic film of the same name starring Dick Van Dyke.

7. LANGSTON HUGHES

Prolific poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist

Langston Hughes is considered one of the fathers of

jazz poetry, a literary art form that emerged in the 1920s and eventually became the foundation for modern hip-hop. In 1954, the 42-year-old Hughes decided to channel his love of jazz into a sort-of-children’s book that educated young readers about the culture he so loved.

The First Book of Jazz was born, taking on the ambitious task of being the first-ever children’s book to review American music, and to this day arguably the best. Hughes covered every notable aspect of jazz, from the evolution of its eras to its most celebrated icons to its geography and sub-genres, and made a special point of highlighting the essential role of African-American musicians in the genre’s coming of age. Hughes even covers the technicalities of jazz — rhythm, percussion, improvisation, syncopation,blue notes, harmony — with remarkable eloquence that, rather than overwhelming the young reader, exudes the genuine joy of playing.

Alongside

the book, Hughes released a companion record,

The Story of Jazz, featuring Hughes’ lively, vivid narration of jazz history in three tracks, each focusing on a distinct element of the genre. You can here them

here.

For more on rare and out-of-print children’s books by famous 20th-century “adult” authors, I really can’t recommend Ariel S. Winter’s beautifully written, rigorously researched We Too Were Children enough.

(Via

Brain Pickings.)

Brain Pickings previously looked at different ways to

Brain Pickings previously looked at different ways to